Table of Contents

Having co-founded Xaira Therapeutics, what experiences prepared you to step in as CEO?

I started my career as an academic. I'm a neuroscientist, by training. My passion was, and continues to be, how the brain gets wired up during embryonic and fetal development; how neurons are formed; and how they find each other and connect up into circuits.

My first faculty position was at UCSF, in San Francisco, and I then moved to Stanford. We worked on trying to identify the molecules that are responsible for wiring up the brain. We - and others in the field - were successful. We identified molecules we called netrins, and I might have continued down that path.

But I became interested in applying the research that I was doing for personal reasons. My father had a stroke and, of course, in a stroke, nerve cells get disconnected. The question was whether some of the mechanisms we'd identified could be helpful in restoring function after stroke. Also, one of my funders was the Paralyzed Veterans of America Spinal Cord Research Foundation.

While I pursued the identification of wiring mechanisms from an intellectual perspective, interacting with those people made me realize that our work could have real benefits in the case of spinal cord injury. So that's what set me on that path, and resulted - after working with some startups, and co-founding one - in me moving to the private sector, about 12 years after I started my lab.

In the early 2000s I went to Genentech to learn how to make drugs. At first, I oversaw about two-thirds of the research organization, and then, became the chief scientific officer. It was really a transformative time for me; being able to continue to do science, but also to immediately apply it to develop therapies that help people, while learning from the best of the best.

I was then recruited back to academia - first, to run Rockefeller University, and then, Stanford - but I stayed involved with biotech, serving on boards, and co-founding a company.

When this opportunity came along, a year and a half ago, it just seemed like an extraordinary moment. AI is transforming all business processes. It's going to, I believe, transform how we discover and develop drugs - taking this somewhat broken, artisanal, endeavor that we have currently, and turning it into more of an engineering discipline, where a lot more of the work can be done in silico, with much higher predictive value.

Being able to bring AI together with my experience in drug discovery and development, I just couldn't think of a better opportunity. So, I leapt at it.

If you think about Xaira, what we're doing is bringing together three groups of people: deep experts in biology, especially disease biology; drug hunters - people who know how to take insights and turn them into drugs; and leading AI scientists, who are working to apply AI to transform those steps.

My time as an executive at Genentech, and in leadership positions in academia, has given me, on the one hand, the background in disease biology and drug discovery; and, just as importantly, over the years, I've learned how to bring together diverse groups of scientists with different backgrounds, and to help them work productively together toward an important, shared goal, for the benefit of patients.

By doing so, we can make new medicines that can't be made today with current methods and also make medicines that can already be made today, but doing it faster.

So, you are combining machine learning with biology. What biological challenges are you trying to tackle first, and why?

We're tackling two biological challenges.

The first is to use generative AI to design antibody therapeutics. As you know, there are lots of different therapeutic modalities. We focused on antibodies because it's where the AI technology is most advanced, right now.

Currently, there are a lot of molecular targets that you'd like to make an antibody therapeutic against, that are refractory to existing methods, typically because they're difficult to screen because of their shape or topology.

AI does not have the limits that current screening methods have, because the AI will make an antibody to a particular part of the protein, and it doesn't matter if it's difficult to screen the protein. AI is not limited in that way.

This is an opportunity for us to make medicines that, otherwise, could not be made, which benefits patients. It also means that, as a company, we can be in a space that isn't as competitive. When you're developing a new technology, you don't want to go for targets that are well served by current methods. Today, we couldn’t compete in those situations, even with AI.

We're developing our technology for areas where current methods fail. Over time, we believe that the methods will become powerful enough that we can compete on any target, but that's the approach that we're taking, from a business point of view. It's beneficial for patients, but also for building our business.

The second biological problem we're focused on is that of target identification. When you're making a drug, you're always making it against something - typically a protein with an intended effect. You have a theory that if you could switch off a particular protein, or boost its activity, you'll have a beneficial effect on the problem you're interested in, whether it's for asthma, cancer, or Alzheimer's disease.

The question becomes: which targets should you go after? And, also, which targets will matter? Even if you have a good target with a good drug, it's typically not obvious as to which patients will benefit the most from that therapeutic.

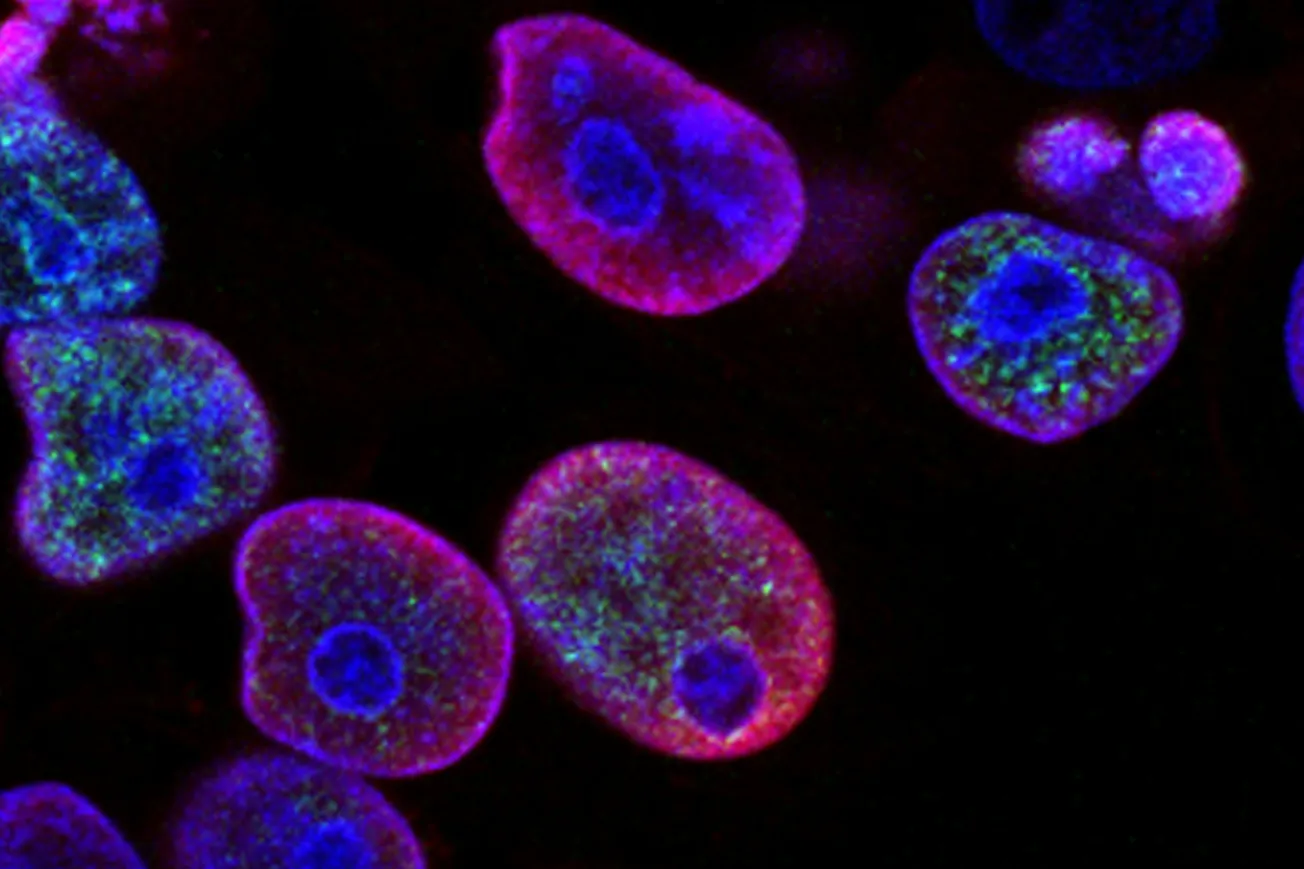

We're interested in developing foundation models of biology that understand cell biology at a causal level. We want to interrogate them, to ask questions like: if the cell is in a disease state, what changes do you have to make, within the cell, to bring it back to a healthy state? That will give you the targets. But then, the question becomes: how does that match up to various patient populations?

We believe that, currently, the methods applied for choosing targets, and matching them to patients, are artisanal. There's a lot of science, of course, but there's also a lot of trial and error and empiricism. In fact, the major sources of failure, in the whole drug discovery pipeline, are choosing the wrong targets, or not figuring out who will benefit, even when you have a good target and drug.

We believe that AI will enable us to take our ability to identify targets, and match them to patients, to an entirely new level; especially if we can develop robust models, by generating and feeding into them large amounts of the right kinds of data, to create causal models of biology in patients.

So that's the second problem we're tackling - improving our ability to identify targets and match them to patients using AI.

When you have AI-designed molecules, how do you ensure that they meet the same standard of rigor as a normal chemical or biological candidate? What do you use to determine whether this model output advances through the pipeline?

In all the work we're doing, unlike some areas in the consumer AI space, there's always a verification step.

If we choose a molecular target, and have the AI generate a drug candidate, we test it in the same way that you would test a drug candidate obtained by any other means. If you look at the different ways of screening to get antibodies, today - whether it's phage, or yeast display, or immunization of humanized mice - what you get is a test candidate, and it remains to be determined whether that candidate has the right properties; the right kinds of affinity; the right kinds of specificity; and whether it behaves appropriately - first, in preclinical animal models, and, then, in human beings.

AI-designed molecules are subject to the same standards that one would apply to any molecular entity.

The beauty of AI is that it learns. When we do those steps, we typically don't look at just one molecule. We look at a panel. Some have the right properties, but some don't. We feed those conclusions back to the model, so that, next time around, it does a better job.

That's the difference between AI design and conventional screening. Conventional screening is ‘Groundhog Day’ - every day is another screen, you do the same thing, and you try to get candidates from out of a massive library. With AI, you can teach the model, at every step, to get better and better.

How are you diversifying your portfolio of models? How do you avoid being locked into one model that doesn't perform in real life?

We keep an eye on what everyone else is doing. Anything public, we evaluate to see if the ideas can augment our work.

You can have a model trained on a certain type of protein. It gets really good at making antibodies to that protein and related proteins, but it doesn't generalize. You've created a specialist model.

We believe that we can make general-purpose models, trained on broad data, that extend to situations the model hasn't seen before. We benchmark at every iteration, to ensure we're not getting good at only a few proteins.

We also work on engineering improvements - to reduce time and improve workflows. We stay alert to ensuring the model is robust and can improve continuously, instead of becoming bespoke and brittle.

What we are beginning to see, with AI-based tools and platforms, is that somebody is first in class, and then, suddenly, there are 10 competitors. What is your moat, and how are you differentiating, or defending yourself from replication?

In AI, you need three things: algorithms, compute, and data. Compute isn't limiting. Algorithms depend on the ingenuity of your team, but you're right, there isn't much of a moat there. Someone may be first, but others can catch up.

What's really limiting in biology is data. Unlike ChatGPT, which can train on all the text on the internet, there's a limited amount of usable biological data available.

For antibodies, for example, we all know about AlphaFold and its extraordinary success, and subsequent developments like RFdiffusion and RFantibody. All of those are trained on the Protein Data Bank, the PDB, which has about 200,000 highly curated protein structures and some complexes.

There's very little data in the PDB on protein-antibody interactions. So, every company can access the public data and take models to a certain point, and that's great. There are a certain number of tasks that can be solved with publicly available data.

We believe that going to the next level and targeting difficult molecules with antibodies, requires additional data. One of the moats will be data, and companies that are clever about which data to generate, to help increase the power of their models, will have a head start.

The same is true for foundation models of biology. There's a lot of descriptive data - single-cell RNA-seq data. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) has curated millions of datasets generated largely by academics. One of our scientists, Bo Wang, our head of biomedical AI, when he was at the University of Toronto, published the first scGPT (single-cell GPT), which is a model that's very good at making descriptive predictions on single-cell RNA-seq datasets, curated by CZI.

You have cells that are diseased, and those that are healthy, and it can tell you the differences. What it can't do is answer causal questions: if a cell is in a disease state, what needs to be changed to bring it back to a healthy state?

The reason that models, like scGPT, fail at causal queries is because they haven't seen causal data and can't derive causality from descriptive data, alone.

So, we've been generating large amounts of causal data. A foundational method that we've been using is Perturb-seq, where we perturb every gene, individually, in cells, and then look at all genes in that cell as a readout. That's 20,000 gene perturbations by 20,000 gene readout. That's the kind of data you need to start building a foundation model, and you need it across many cell types.

Back in June, we industrialized the method and released the first two Perturb-seq datasets. We made them publicly available. It was more Perturb-seq data than had been published by the entire world up to that point, and, since their release, we've generated about three times as much, again!

We're going to need large amounts of data, and again, that will give an edge to those who generate the right data and deploy it in the right ways.

Speaking of an edge, you emerged from stealth with a billion dollars in initial funding, which is a lot more runway than a typical biotech startup. How did that capital shape the strategic timeline, and how do you allocate it?

With the accelerating advances in AI, we saw an extraordinary opportunity to transform how we discover, and develop, drugs. As I mentioned, we wanted to tackle all three steps of the drug discovery process: target ID, drug making, and patient stratification.

We're a platform company working in these overlapping areas, but we also believed that the best measure of success was to show that we could apply the platform to develop a pipeline of differentiated therapeutics. We didn't want to compromise one for the other. For that, we needed a large capital raise.

In a typical small biotech, you raise enough money to start a platform or focus on one product. If you're a platform company, you bring the platform to a certain point, and then, to monetize it, you have to develop a therapeutic. Once you start developing a therapeutic, you only have capital to develop one product, and the platform gets deprioritized.

Time and time again, in biotech, we see platform companies pivoting into becoming product companies. Those are fine paths, but our ambition was greater. We wanted to go the distance as a platform and also prove it by making multiple therapeutics. We wanted enough capital to execute on both, without compromising either, or not to return to capital markets until we had multiple therapeutic candidates progressing in the clinic.

Over the next one to two years, which milestones are you going to use to demonstrate value in the company?

We haven't disclosed timelines publicly, but, at a high level, we're focused on developing models that are powerful enough to make therapeutics against very hard-to-drug targets with strong validation, and move those toward, and into, the clinic.

We're also focused on developing the first foundation models of biology that provide insights into not just normal cell function but also into disease processes - identifying targets and matching them to patients.

Those are our north stars, and we're executing toward achieving those goals every day.

Can you talk about the difference between traditional drug R&D versus AI-driven discovery? How much leverage do you have there?

There are two things that we're doing in the short term, with molecular design.

We're trying to drug undruggable targets. There, the value proposition is being able to make therapeutics others can't currently make, because current technologies are not well adapted to those targets. So, it's not a direct comparison; you're creating value in a category where you may have a lot of runway by yourself.

We also believe that, over time, which we’re already starting to see, the methods can become powerful enough that we can teach the models what you need for a therapeutic. The AI will provide a time advantage over current methods for making antibodies. The two value propositions are: make more antibodies faster and make antibodies against hard targets.

We have an investment in building the platform, but, once the platform is established, we believe the economics will be attractive.

Partnerships with big pharma?

We think partnerships are terrific! There are lots of reasons to do them. We're interested in partners who can accelerate our programs or expand our scope.

Some partners have deep expertise in specific therapeutic areas, including preclinical assays or patient registries. Some trials are long or expensive, so partnerships make sense.

We see partnerships as a way to accelerate and extend our scientific impact.

Some AI-bio companies have struggled financially. Costs are high, and it's been hard to persuade big pharma to fund clinical phases. How will you survive when others have stumbled?

Partly because of my background. I come from drug discovery at Genentech and have been involved with several startups. I've been a senior advisor, a co-founder, and a board member.

One of the things that excited me about Xaira was the vision of applying AI to drug discovery, but also that, from day one, we needed to be able to make drugs. The technology had to be advanced enough that we could make drugs immediately, and we had to be strategic about which targets to go after.

Those elements are baked into Xaira from the start.

We decided to go after validated targets that are hard to drug. We don't want to stack biological risk on top of technical risk. We're being strategic about resources, trying to transform drug discovery, but also generate value from the start. It's strategy plus disciplined tactics.

Before handing the asset over to big pharma at the IND stage for a royalty?

We have some targets that we believe could be solo opportunities, and that we could develop ourselves. Others, we think would be partnering opportunities.

With the capital we have, we don't have to settle. Many small biotechs trade long-term upside for short-term cash. We can take the time to find partners who are willing to preserve upside, like a 50–50 deal. There's a well-worn path to that.

The model of out-licensing for cash, and a small royalty, helps you survive day-to-day, but doesn't create long-term upside. We can preserve that upside. We're capitalized and organized to do that.

By the way, your question is very fair. It's one I've thought about for decades, to make sure we create a company that can go the distance.

When you strip it down, you've got to be willing to walk away from a deal. If you have cash in the bank, you can do that.

There are pros and cons. A small capital base enforces discipline, but also leads to pitfalls - unexpected obstacles, raising capital at the wrong time, keeping molecules alive when they shouldn't be, or giving away upside.

With a large capital base, we can avoid those pitfalls. We can pause, or kill, therapeutics that aren't looking good. We don't have to settle. But we also need discipline, so we don't become complacent.

We need the hunger of a cash-starved startup, without the same constraints.

Finally, what do you see as being the biggest challenge during your tenure as CEO, and what plans do you have in place for that?

I think the biggest challenge, and the most interesting, is bringing together diverse individuals around a common problem: therapeutic-area biologists and specialists; drug hunters; and frontier AI scientists.

Today, almost no one is bilingual or trilingual across these domains. So, making sure people work together productively really is job number one for me.

It's also what gives me the greatest joy. It's exciting to see interactions among scientists making a particular medicine - AI scientists being amazed at target selection; drug hunters astonished by the AI; biologists fascinated by drug discovery and vice versa.

What motivates everyone is knowing that, if we're successful - which we will be - this will help patients. Ultimately, it's about bringing together the best minds, and enabling them to be productive, so as to achieve the goal we all aspire to: transforming how we discover and develop drugs, so we can better serve patients and conquer disease.

Comments